Enhanced sharing economy model for sustainable national development

The Sharing Economy (SE) is a constantly evolving and fast growing economic principle that enables organisations and individuals with diverse assets and services around the world to share and match these in real time. By utilising and optimising effective capacity sharing, mutual benefits are maximised.

Farronato et al (2015) argues that SE completes transactions between supply and demand, drastically reduces middle-man involvement, honing a trusted network between complete strangers through digital platforms. SE is also known as Peer-to-Peer based sharing or collaborative consumption between two individuals.

It also highlights the ability and perhaps the preference of individuals to rent or borrow goods rather than buy and own them (SearchCIO, 2019), which is a more sustainable form of consumption (Newlands, Lutz and Fieseler, 2018). With resources becoming increasingly scarce, maintaining resource demand is challenging, while on the converse, some owned resources are not fully utilised. Resources assumed to be personal are now being added to share and earn within the SE (Harris, 2017) and access to ownership is broadened. This ultimately promotes better practices for sustainable consumption.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) models are re-shaping global industry with an estimated growth trajectory of USD 0.5Tn by 2025 (The Statistics Portal, 2018). Efficient sharing of services and assets among peers in real time through highly responsive smart digital platforms are reliable and cost effective in this environment (Benkler, 2019).

The SE has grown exponentially over the past few years (Ahsan and Mujtaba, 2020), disrupting numerous industries and redefining the fundamentals of employment. It has promoted economic opportunities for individuals, empowering them into micro-entrepreneurs and allowing workers to enjoy flexibility and freedom (Martin, 2016). Expected growth in the US alone will reach up to 9.2 million by 2021 (Molla 2017).

The SE model integrates diverse capabilities of numerous industries including accommodation, transport, skill, trading, funding, lending, energy and retirement. Airbnb, BlaBlaCar, Fiverr, oDoc, Helios, Crowd-Funding and Zopa are prime examples of P2P in the SE. For instance, AirBnb, the world’s largest accommodation provider, owns no real estate but has five million listed rooms, while Marriot, the second largest owns one-third. This is how the SE disrupts industry.

The SE is ideal for Sri Lanka’s economic development. Increasing efficacy and utilisation of resources in a P2P environment via an enhanced model which suggests using a collective of people’s resources rather than of a single individual is beneficial.

These resources could be in HR, skills, financial and tangible assets of land, vehicles and buildings. The country also possesses significant quantities of; underutilised resources including property, agricultural land and skilled and non-skilled human resources, which if optimised via the SE model, can economically benefit Sri Lanka.

In the P2P sharing economy model, resources are shared between 2 peers (supply and demand) and therefore the particular resource has to be a ready-to-share (complete) resource. By listing a property on ‘AirBnb for example, you must own a complete house but can rent under-utilised space. However, in the Sri Lankan context, ready-to-share under-utilised resources may be limited as the resource itself may not be a complete product or service.

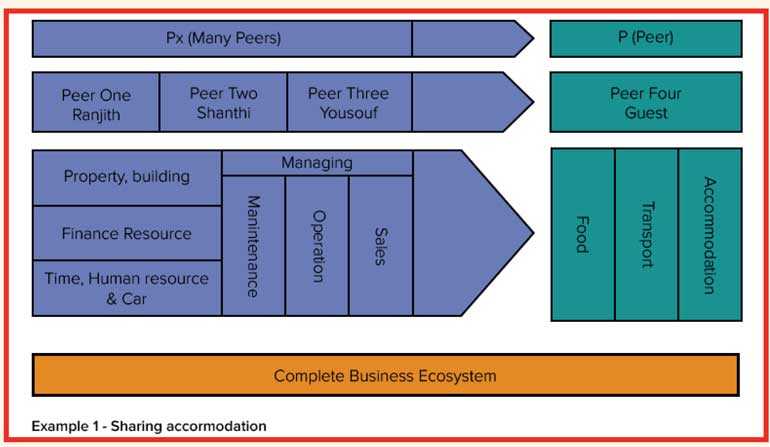

In the proposed model, to extend the P2P by adding a new element ‘x’ to the beginning to represent multiple peers, (Px2P) that is ‘’ManyPeers–2-Peer’’ is expected to significantly increase the effectiveness in the Peer-2-Peer sharing economy. It is also expected to empower more individuals as micro-entrepreneurs than in P2P.

The proposed Px2P for example could be a small group of people, each owning limited under-utilised resources. Together they can effectively utilise these resources marketing a competitive product or service. Collating clusters of small under-utilised but related resources (many peers), will create a complete saleable product or service, but will encompass a micro entrepreneur synergy.

Using AirBnB as a sharing accommodation example, Ranjith (Peer One), a busy corporate executive has space to build a self-sustaining studio room to his house, however, with limited time and financial resources. Shanthi (Peer Two) who has financial resources and Yousouf (Peer Three), a retired gentleman with time availability and a car to share, get together with Ranjith, build the studio room and list it on AirBnB. All three Peers gain benefits proportionately with the monthly revenue generated by letting the studio apartment to guests (Peer Four). Refer to Example 1.

Another example is the Ramachandran family. Ramachandran is employed full time and his wife is a stay at home mother, looking after three school-going children. They live in semi-rural Sri Lanka with a backyard of about 10 perches. However, disposable income and time is limited.

A neighbour, Perera who has funds, approaches the Ramachandrans to construct a greenhouse of 2,000 sq. ft. He also purchases seeds to plant bell pepper, ginger, and chillies and invests in their upkeep. Mrs. Perera undergoes training in horticulture, marketing and managing the greenhouse from a local agriculture department instructor. She is able to invest the time required for this, knowing that the produce can be sold at reasonable prices at the nearest supermarkets or at the agricultural land itself.

The proposed model (Px2P) maximises on limited under-utilised resources which are scattered and may not have had value or the prospect of additional income generation. In the two examples above, these individuals with scattered resources become micro entrepreneurs with a small but sustainable business model.

This model, while helping these small businesses’ sustainability, also reduces the ‘middle-man’ involvement of micro-finance companies who charge high interest rates. Each business belongs to all three individuals as a result of sharing their idle capacity. It enables the making of a Collaborative Economy, moving away from the conventional concepts of P2P in SE.

This model can also be applied in large scale businesses by establishing trust between stakeholders using methods like; get Government ground level offer (Agriculture instructors) involved as another peer (P) in the value chain.

(The author, PDCN Wickramasuriya is a Sharing Economy researcher on global P2P business models. You can reach him on cnavinda@gmail.com.)

Bibliography

Ahsan, Mujtaba. (2020). Entrepreneurship and Ethics in the Sharing Economy: A Critical Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics. 161. 10.1007/s10551-018-3975-2.

Benjaafar, S., Kong, G. and Courcoubetis, C. (2019). Peer-to-Peer Product Sharing: Implications for Ownership, Usage, and Social Welfare in the Sharing Economy. pubsonline.informs.org. [online] Available at: https://pubsonline.informs.org/doi/abs/10.1287/mnsc.2017.2970 [Accessed 3 Jan. 2019].

Benkler, Y. (2019). What’s Next for the Sharing Economy?.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v =DNBY8yNXGoA&t=62s [Accessed 14 Nov. 2018].

Botsman, R. (2016). The Sharing Economy with Rachel Botsman. [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0MHrkeG5HiQ [Accessed 18 Nov. 2018].

Cañigueral, A. and Heimans, J. (2017). The “sharing” economy. [online] Eesc.europa.eu. Available at: https://www.eesc.europa.eu/resources/docs/albert-canigueral.pdf [Accessed 28 Dec. 2018].

Fang, Z. and Huang, L. (2019). Boosting Sharing Economy: Social Welfare or Revenue Driven?. [online] ResearchGate. Available at:

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301880653_Boosting_Sharing_Economy_Social_Welfare_or_Revenue_Driven [Accessed 21 Dec. 2018].

Farronato, C., Levin, J., Brusson, N., Abele, M., Lacangelo, S. and Schmid, C. (2015). The sharing economy New opportunities, new questions. Global Investor. Zurich: Investment Strategy &Research, pp.1,7.

Hagan, T. (2018). Sharing Economy and its Impact on the Transportation Sector. [online] Startupbootcamp. Available at: https://www.startupbootcamp.org/blog/2018/06/sharing-economy-impact-transportation-sector/ [Accessed 22 Nov. 2018].

Harris, S. (2017). The Rise of the Sharing Economy.

Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Dm3ZDnT9Zag [Accessed 15 Nov. 2018].

Jenkins, K. (2018). Platforms in Aotearoa, OUR FAST GROWING SHARING ECONOMY. Policy Quarterly – Victoria University Open Journal System (OJS)., 14(1), pp.13-15.

Molla, R. (2017). The gig economy workforce will double in four years. Recode. Retrieved May 25, from https://www.recod e.net/2017/5/25/15690 106/gig-on-deman d-econo my-worke rs-doubl ing-uber.

Newlands, G., Lutz, C. and Fieseler, C. (2018). Power in the Sharing Economy. Report from the EU H2020 Research Project Ps2Share: Participation, Privacy, and Power in the Sharing Economy. Oslo: BI Norwegian Business School, pp.2, 17.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. and Thornhill, A. (2012). Research methods for business students. 6th ed. Harlow: Pearson, pp.162-163, 134-136, 128-129, 179.

SearchCIO. (2019). What is sharing economy?. [online] Available at:

https://searchcio.techtarget.com/definition/sharing-economy [Accessed 29 Dec. 2018].

Sundararajan, A. (2019). The Sharing Economy, The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-based Capitalism – Principus. Retrieved 5 January 2020, from https://principus.si/2019/03/17/arun-sundararajan-the-sharing-economy-the-end-of-employment-and-the-rise-of-crowd-based-capitalism/

Sundararajan, A., Jacobides, M., & Van Alstyne, M. (2019). Platforms and Ecosystems: Enabling the Digital Economy. Retrieved 7 January 2020, from

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Digital_Platforms_and_Ecosystems_2019.pdf

https://www.researchgate.net/. (2019). Examining “peer-to-peer” (P2P) systems as consumer-to-consumer (C2C) exchange. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/241668507_Examining_peer-to-peer_P2P_systems_as_consumer-to-consumer_C2C_exchange [Accessed 7 Dec. 2019].

Kaushal, Leena. (2017). Book Review: Arun Sundararajan, The Sharing Economy: The End of Employment and the Rise of Crowd-Based Capitalism. Vision: The Journal of Business Perspective. 21. 238-239. 10.1177/0972262917712390.

Rinne, A. (2019). 4 big trends for the sharing economy in 2019. [online] World Economic Forum. Available at: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/sharing-economy/ [Accessed 15 Dec. 2018].

San, D. (2019). How The Sharing Economy Is Shaping The Future Of Retail. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/theyec/2019/01/24/how-the-sharing-economy-is-shaping-the-future-of-retail/ [Accessed 16 Dec. 2018].

The Statistics Portal. (2018). Value of the global sharing economy 2014-2025 | Statistic. [online] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/830986/value-of-the-globalsharing-economy/ [Accessed 12 Jun. 2018].

World Economic Forum. (2018). What’s Next for the Sharing Economy? [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DNBY8yNXGo A&t=39s

Zervas, G., Proserpio, D. and Byers, J. W. (2017) ‘The Rise of the Sharing Economy: Estimating the Impact of Airbnb on the Hotel Industry’, Journal of Marketing Research, 54(5), pp. 687–705. doi: 10.1509/jmr.15.0204.Q